He saw that inductive reasoning and a belief in causality are not based on reason, but based on habits.

Inductive reasoning refers to methods of reasoning where the conclusion does not have a deductive certainty, but rather, has a degree of probability. This is as opposed to deductive reasoning (such mathematical induction), where the conclusion is certain. For example, inductive reasoning includes how X% in a sample set would map to X% of the whole set.

He believed in (1) empiricism, (2) philosophical skepticism (as opposed to rationalism) and (3) metaphysical naturalism.

As opposed to philosophical rationalists, he said that passion, rather than reason, governs human behaviour. He also said that ethics are based on feelings rather than some moral principle.

He also pointed out that those who report miracles are most likely doing it for (1) the benefit of their religion, or (2) for fame; and that they mostly only come from ignorant and barbarous nations. While he leaves the possibility open, he gives several arguments to point out that they have never occurred in history. In Section 10 of An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, Hume defines a miracle as “a transgression of a law of nature by a particular volition of the Deity, or by the interposition of some invisible agent”.

He is held to be the first European philosopher to have clearly expounded the “is-ought” problem, which is that one form a normative conclusion of an “ought” (what one should do) directly from an “is” (what is). This is called Hume’s Fork or Hume’s Law (explained below).

His compatibilist theory of free will takes causal determinism as fully compatible with human freedom. He also denied “argument from design” for God’s existence.

Immanuel Kant credited Hume as the inspiration that awakened him from dogmatic slumbers.

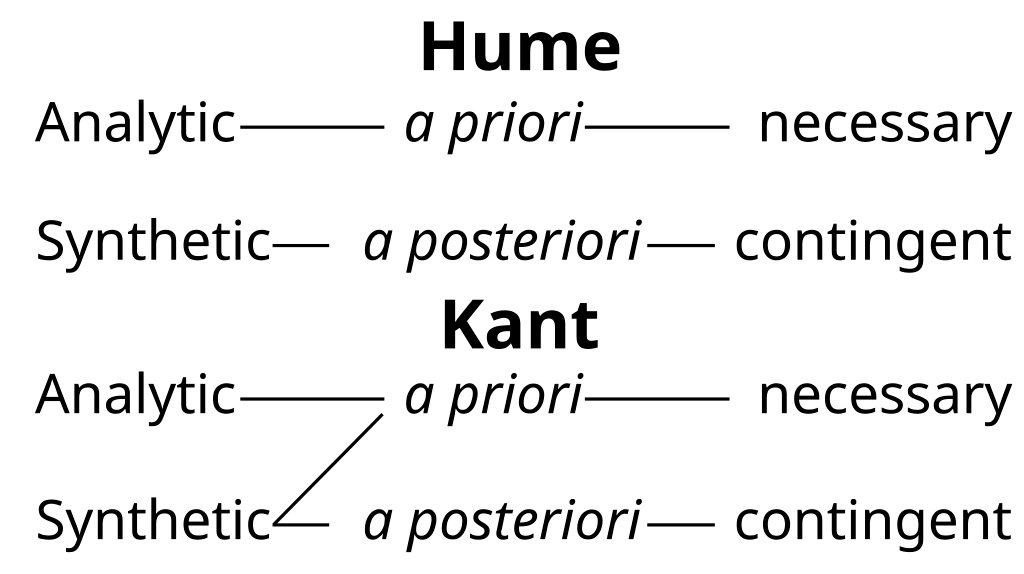

Hume’s Fork, as described by Kant, and Kant’s Trident

Basically, it is a relation between “relations of ideas” and “matters of fact”.

It proposes three things about a statement:

(1) Its meaning is either “analytic” or “synthetic” (2) Its truth (agreement with reality) is either “necessary” or “contingent” (3) Its purported knowledge is either “a priori” or “a posteriori”

“Analytic” refers to statements are true or false due to their meaning. For example “bachelors are unmarried” is true, because bachelors are by definition, unmarried. Similarly “all bodies occupy space” is valid because that is the definition of a body.

“Synthetic” refers to statements which have their truth values due to their relation with the world. For example, “bachelors are alone” is synthetic, because bachelors are found to be “alone”, but it has no basis in the definition. Similarly, “all bodies are heavy” is inferred by Newton’s laws of gravitation.

Further, Kant explains “a priori” and “a posteriori”. I had explained them here, but I’ll explain it again.

“A Priori” refers to statements that do not require experience to be valid. For example, “all bachelors are unmarried”, or “7+5=12”. “A posteriori” refers to statements that require experience to be valid. For example, “all bachelors are unhappy” or “tables exist”.

Based on these two sets of categories, he first proposed four categories of statements:

(1) Analytic a priori (2) Synthetic a priori (3) Analytic a posteriori (4) Synthetic a posteriori

But (3) is self-contradicting. So ruling it out, he said that all statements are of three types: (1) Analytic a priori, (2) Synthetic a priori and (3) Empirical or “A posteriori”.

Example of “Analytic” and “A posteriori” statements were given above. For “Synthetic a priori”, he gives the examples in mathematics and physics.

He says that “synthetic a priori” statements cannot be verified. But he states that they are possible, and that is a defense of the field of metaphysics.

Hume on the other hand, does not hold “synthetic a priori” statements to be true. Hence, we get the following image of Hume’s fork and Kant’s pitchfork or trident:

In the 1920s, logical positivists sought to discard this by asserting that only statements that can be verified, i.e. Analytic a priori and Synthetic a posteriori statements, could be meaningful. They held to Hume’s fork, and hinged it at language by the analytic-synthetic division, by presuming that by holding on to analyticity, they could develop a logical syntax entailing both necessity and aprioricity on one end, and demand for empirical verification on the other end.

In the 1950s, Willard Van Orman Quine undermined this analytic-synthetic division, by pointing out ontological relativity, as every statement has its meaning dependent on (1) a vast network of knowledge and beliefs, and (2) the speaker’s conception of the whole world.